Indonesian deforestation and plantation expansion slow

Opportunity to improve planning and management of oil palm

MARTEL, France (March 29, 2022) – Slowing deforestation rates in Indonesia were linked to a drop in the market value of crude palm oil, an indication that trends reflect fluctuating commodity prices, according to a new study published on Tuesday in PLOS One journal.

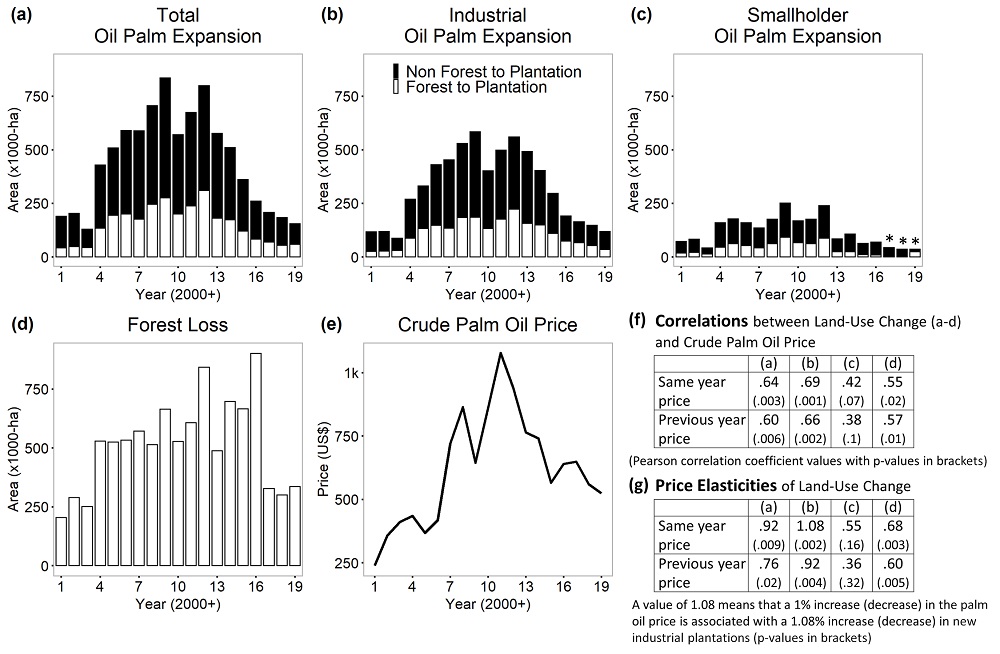

Research led by TheTreeMap, a firm studying tropical deforestation, shows that expansion of industrial plantations and forest loss was closely correlated with palm oil prices. Through a satellite survey conducted from 2001 to 2019 over Indonesia, scientists from seven countries representing six organizations took stock of and estimated the impact of large-scale and smallholder oil palm plantations on natural old-growth, or primary, forests.

“Deforestation rates fell below pre-2004 levels from 2017 to 2019, providing an opportunity to focus on sustainable management,” said David Gaveau, founder and managing director of TheTreeMap.

“The price of palm oil has doubled since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, making effective regulation and oversight key to preventing further forest conversion.”

Historically, a price increase of 1 percent was associated with a 1.08 percent increase in new industrial oil palm plantations and a 0.68 percent increase in forest loss.

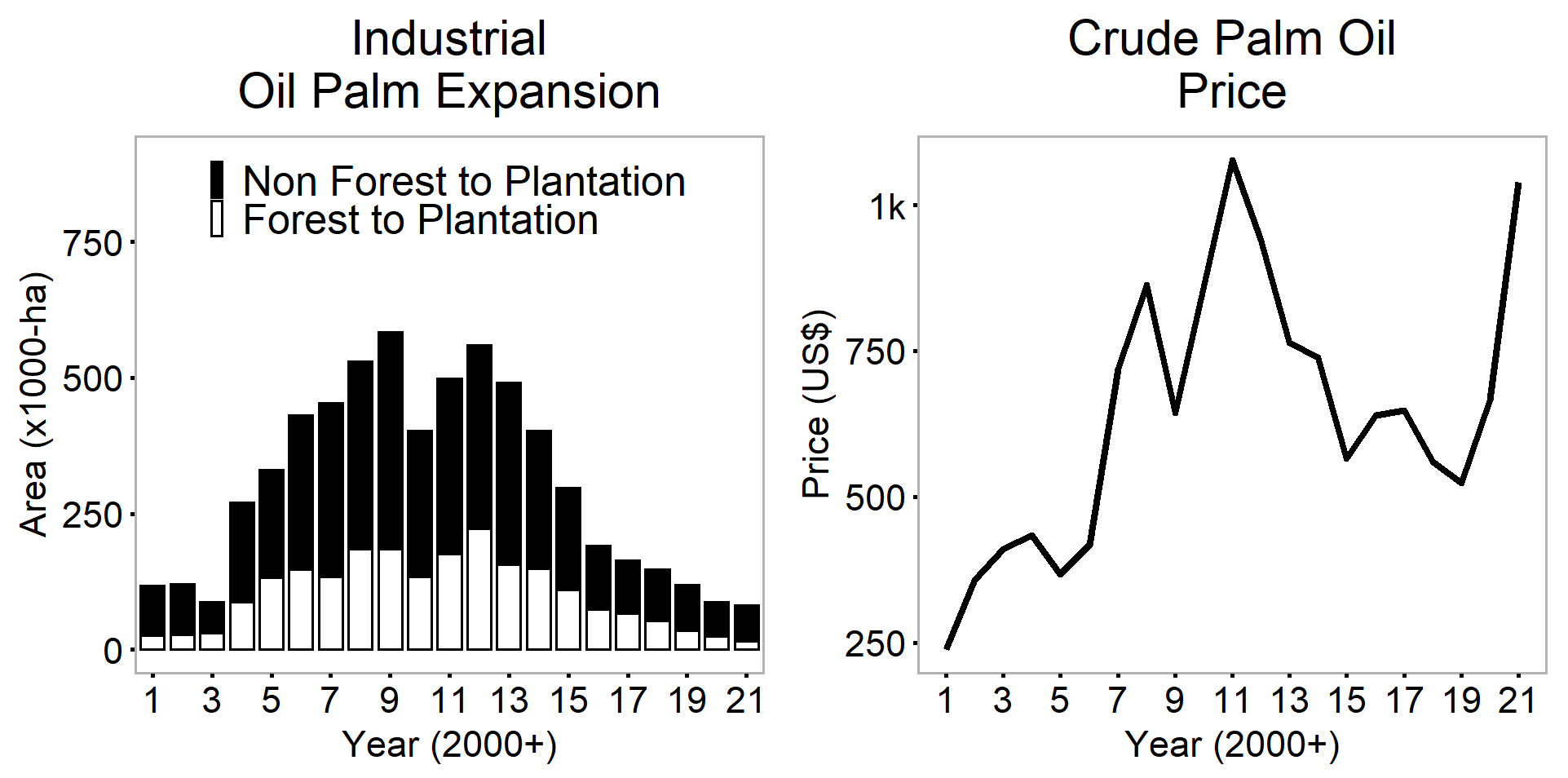

The recent spike in palm oil prices has not, however, been accompanied by an expansion of new palm oil plantations, a cause for cautious optimism, the researchers said.

“But it’s as yet too early to tell whether the pandemic represents a watershed, with palm oil expansion becoming less sensitive to the price change,” said co-author Arild Angelsen, an economics professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

“This pioneering effort – for the first time – presents an annual time series showing the expansion of industrial and smallholder plantations, forest loss, and their overlap from 2001 to 2019 across Indonesia,” said co-author Bruno Locatelli from France’s International Cooperation Center in Agricultural Research for Development (CIRAD).

Industrial plantations expanded more than 6 million hectares (Mha) – a rate much faster than smallholder plantations, which expanded only 2.3 Mha – and led to almost three times as much forest conversion, he added.

Over the study period, the area mapped under oil palm doubled – reaching more than 16.2 Mha in 2019. Of this area, 64 percent was managed by industrial plantations and 36 percent by smallholders.

Indonesia produces about 50 percent of all palm oil worldwide. This oil is used in many of the packaged products found in supermarkets, including ready meals, baked goods, chocolate, cosmetics, and shampoo. It is also used as animal feed and – increasingly –as a biofuel.

Conversion of tropical forests into oil palm plantations has been seen as a major cause of deforestation and biodiversity loss, putting livelihoods, birds and endangered animals such as orangutans, tigers and elephants at risk.

“The slow-down in expansion offers a chance for the Indonesian government and other stakeholders to work together to improve planning and management of oil palm and other plantations,” said co-author Timer Manurung, from Auriga Nusantara. “Encouraging good practices and transparency will serve future generations.”

The researchers make a conservative estimate that oil palm was responsible for one-third of Indonesia’s loss of old-growth forests (9.79 million hectares cleared, or 11 percent of forest area in 2000) over the last two decades.

Douglas Sheil, professor of Forest Ecology and Management from Wageningen University and Research, a co-author, underlined that the forests in Indonesia, generally considered the third biggest after Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo, are some of the most special in the world.

“I’ve been fortunate to work in these forests, getting to know local people and seeing some of the region’s unique and wonderful biodiversity – the loss of these forests, cultures and species is a loss for the world,” he said, adding that a fair and nuanced approach to palm oil and similar forest-risk commodities is vital.

In 2011, Indonesia introduced a national moratorium on developing oil palm plantations in primary forests. It was extended indefinitely in 2019, and in January 2022 the Ministry of Environment and Forestry cancelled the permits of 137 oil palm companies (Decree No. 1/2022).

Updated data to 2021, gathered after the study period analyzed in the new Plos One journal article, indicate that palm oil-driven deforestation is now at a 20-year low despite rapidly rising CPO prices. As prices soared to >$1,000 per ton in 2021, companies converted just 15,540 hectares of “primary” forest to industrial oil palm. High production costs, market uncertainties, and regulations appear to underline these changes.,By comparison, 224,100 hectares were converted to oil palm in 2012 when prices were also around $1,000.

“While the long-term situation remains unclear, recent trends are good news for Indonesian forests,” Gaveau said.

OTHER KEY FINDINGS

- More plantations were generally established in areas cleared before 2000 (5.39 Mha).

- Only in Indonesian Papua did most new plantations replace forests.

- Kalimantan experienced the highest share of forest conversion to oil palm (36 percent – 40 percent), followed by Sumatra (29 percent -31 percent), Papua (26 percent – 27 percent) and Sulawesi (6 percent -7 percent).

- In Sumatra and Sulawesi, industrial and smallholder driven conversion were similar, while industrial conversion dominated Kalimantan and Papua.

TheTreeMap endeavors to protect tropical forests through scientific research and advanced monitoring platforms. We are cartographers, remote sensing engineers, software developers, and field investigators. We empower civil society with the tools to detect deforestation in real-time and ensure what happens on the ground is fair, transparent, and democratic. We build systems that check the deforestation footprint of agribusinesses in tropical forests to ensure sustainable production. Our work is based on the premise that no one wants food and other products to be the cause of forest destruction.