New highway may strip 4.5 million hectares of forest by 2036 in Tanah Papua

New Guinea, the world’s second-largest island, hosts extensive old-growth forests, including mangroves and peat swamps. It has more plant species than any other tropical island. It is also home to diverse human cultures, each with their own relationship to nature, and until recently human impacts have been small.

The island is divided – in the west, the provinces of West Papua and Papua make up Indonesian New Guinea, known as Tanah Papua and in the east, it is the independent country of Papua New Guinea.

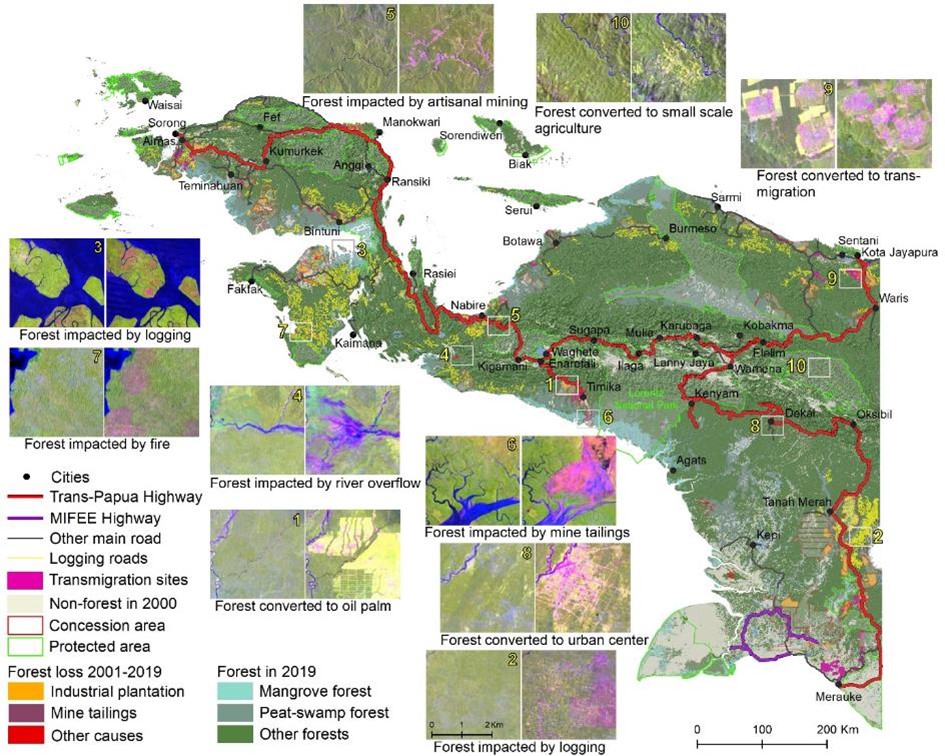

In our new study published on 07 September 2021 in Biological Conservation, we used satellite imagery to examine annual forest loss, road development and plantation expansion from 2001 to 2019, then developed a model to predict future deforestation.

Eighty-three per cent of Tanah Papua remained forest in 2019. This area represents 42% of Indonesia’s forests and is the Asia Pacific region’s largest area of intact old-growth forest.

The model predicts 4.5 million hectares (Mha) – around 13% of the total 34.29 Mha of forest – could disappear by 2036 if Tanah Papua follows the same trajectory as Kalimantan. That’s a result of the development of thousands of kilometres of highway in a project known as “Trans Papua”.

The highway project and its impact

We mapped 3,887km of Trans-Papua Highway (officially, Trans-Papua is 4,330km long.)

This included a 202km road section through the Lorentz National Park, a World Heritage site. In 2019, the opening of Trans-Papua Highway was nearly complete (red lines on the map above), though 51km remained unopened.

Many are concerned that the highway, and other roads, are built to benefit powerful commercial interests and not Indigenous people and will accelerate forest conversion as seen in Sumatra and Kalimantan.

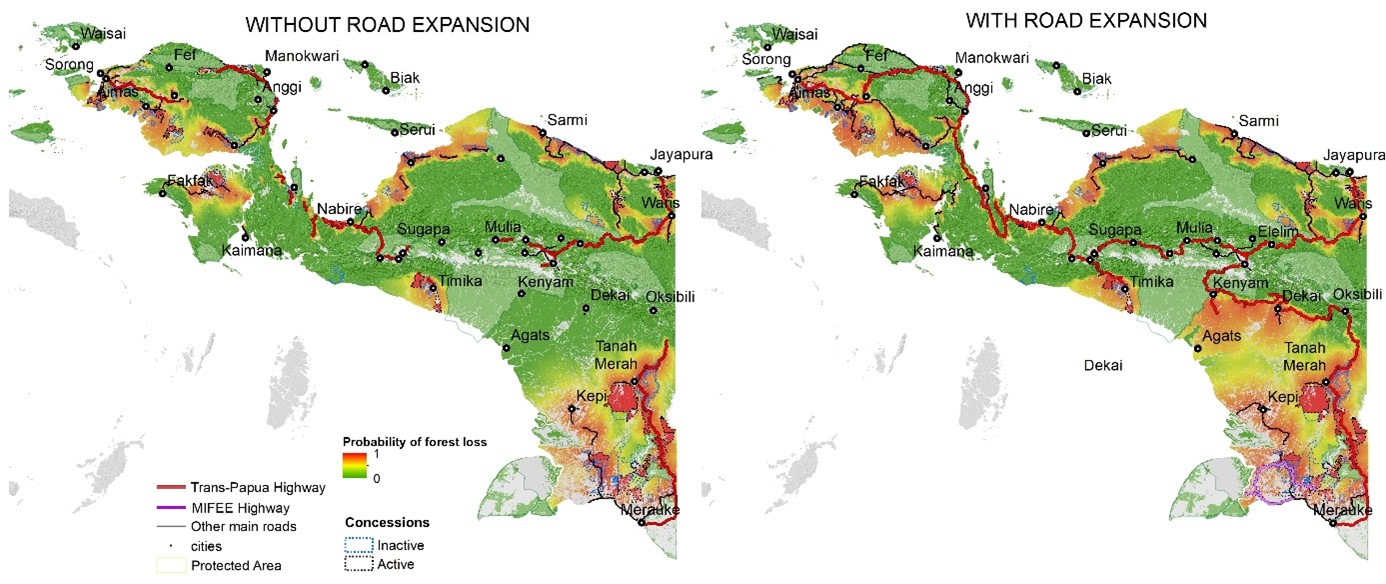

The model shows significant deforestation occurred near existing roads and indicates how new roads are likely to encourage more extensive deforestation in lowland areas. The construction of new roads increased the area of forest at risk of deforestation (red areas on the maps below) by 30% compared to the hypothetical scenario of halting such developments.

Lowland forests near the cities of Dekai and Kenyam – located in central Papua Province – experienced the highest augmented threat.

Roads generally attract interest from plantation companies and from other extractive industries, such as mining, because they ease access and transportation.

Companies invest in new plantations and new mining sites, processing plants, secondary roads and other infrastructure associated with developing these industries. These investments attract workers and their families from elsewhere, requiring more infrastructure and thus more land and more deforestation.

in Kalimantan, Sabah and Sarawak on the island of Borneo, we had already examined forest loss, road development and plantation expansion using satellite imagery over four decades.

Logging, fire, and clearing land for plantations have left a third of Borneo’s tropical rainforest deforested.

VIEW IN ATLAS before

VIEW IN ATLAS before So, what can be done?

The Trans-Papua highway is nearly complete, and many local people aspire to reduced isolation. But that doesn’t mean we should be resigned to extensive forest clearance.

In Papua, the roles of local communities and Indigenous peoples are influential in guarding and protecting nature. And Indonesia’s law has recognised this.

The 2012 decision of the National Constitutional Court (35/PUU-X/2012) recognised the rights and authority of local communities over their ancestral territories as consistent with Indonesia’s constitution.

Respecting the rights of locals, the governors of Papua and West Papua Provinces signed the Manokwari Declaration in 2018.

The declaration requires local governments to conserve at least 70% of the region, and to engage in consultative and information-based conservation planning and management that ensures “environmentally appropriate” infrastructure developments while also protecting the rights and roles of Indigenous peoples.

Under this declaration, and a national moratorium ordering a review of existing permits, the provincial government of West Papua recently revoked permits for 12 oil palm concessions. More such interventions are likely.

The move represents an important step towards recognising the rights of Indigenous peoples and preserving natural habitats in West Papua.

What we need is to build conservation and development opportunities around what Indigenous Papuans themselves find important and desirable.

Effective, consensual and frequent engagement between local people, or their elected representatives, and all layers of government will be key to ensure alignment of local, regional and national development planning to avoid the less-desirable consequences of development seen in Sumatra and Kalimantan and preserve the rich biological and cultural heritage of this remarkable region.

Some sections of this story originally appeared in an article published in The Conversation