Land Clearing in Papua: 2024–2025 Trends and Drivers

KEY FINDINGS

- Satellite imagery and land-use data reveal where land clearing occurred in Papua during 2024 and early 2025, which ecosystems were affected, and which projects and companies were responsible.

- Primary forest loss in Papua rose 10% from 2023 to 2024, reaching 25,300 ha. Preliminary 2025 data indicates the pace is accelerating.

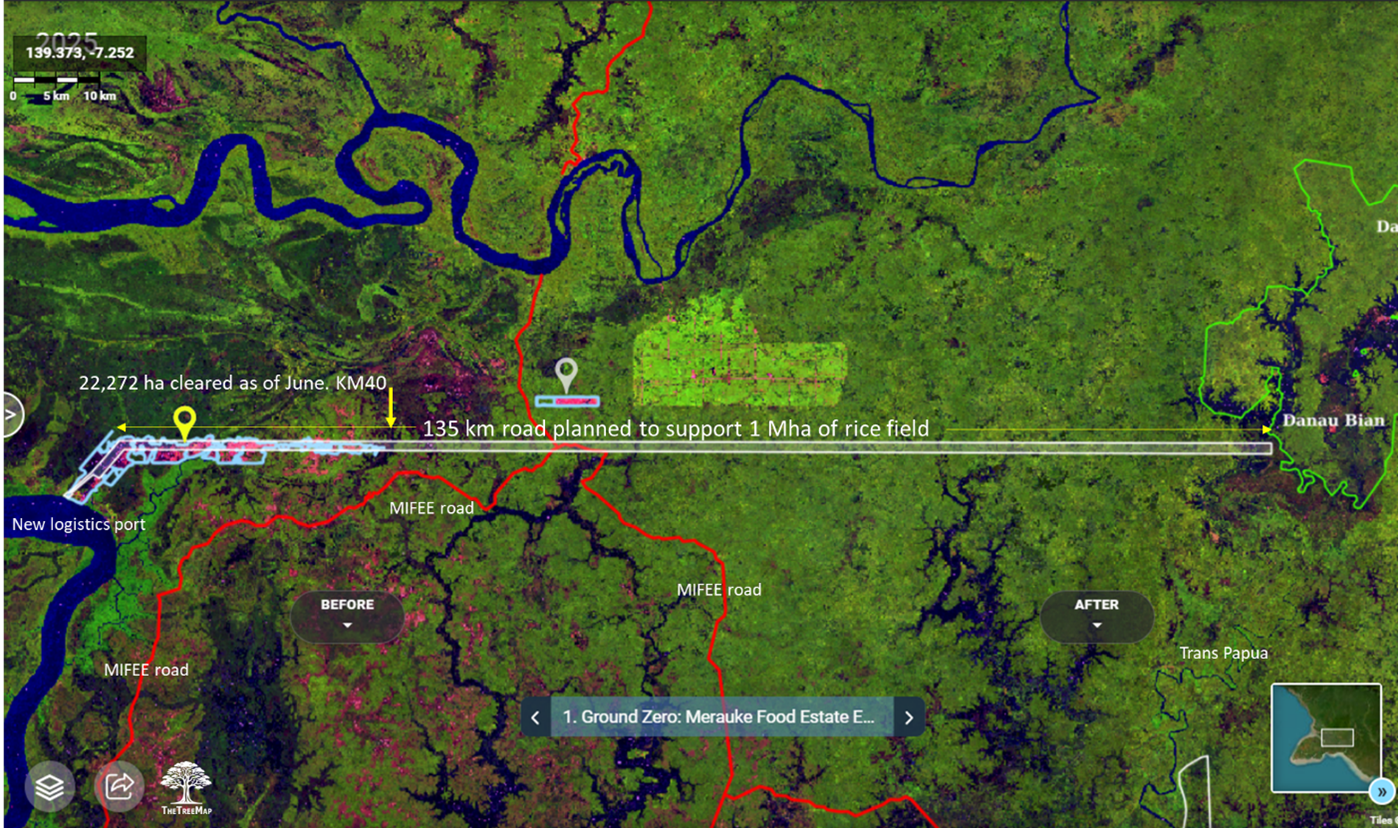

- The Merauke National Strategic Project (PSN) was the top deforestation driver in 2024, causing 5,936 ha of primary forest loss (24%). By mid-2025, PSN-related forest loss reached 9,835 ha.

- From Jan 2024 to June 2025, the Merauke PSN cleared 22,272 ha of natural ecosystems, including forest (9,835 ha), Melaleuca swamp, savanna, and grassland, still far below the 3 million ha target.

- Oil palm was the second-largest deforestation driver in 2024, with 3,577 ha cleared, mainly in Sorong. By mid-2025, oil palm clearing matched 2024 levels, indicating rising pressure.

- The greater threat of Merauke PSN lies ahead: by June 2025, 40 km of a planned 135 km road had been built. Once completed, it will connect to the existing MIFEE and Trans-Papua highways, opening access to forests and dormant transmigration sites.

- The Jhonlin, Fangiono and Salim groups are the main actors driving land clearing in Papua

SETTING THE SCENE

Merauke, this region of southern Papua, remains largely intact — protected by its remoteness, extreme climate, strong Indigenous presence, and a diverse mosaic of inaccessible wetlands, Melaleuca swamp forests, natural grasslands, wooded savannas, and dense primary forests, including mangroves, dryland forests and peat-swamp forests.

But its inclusion in Indonesia’s National Strategic Projects (PSN) is changing that. Backed by national interest status, PSN projects benefit from fast-tracked permits, minimal oversight, and a powerful development mandate.

After a brief slowdown in the early 2020s, 2024 marked a turning point, as large-scale land-clearing projects surged under the current administration. At the centre of this shift is the Merauke Food Estate, a revived PSN initiative. According to official documents obtained by Pusaka and press readings, the Merauke Food Estate plans a new 135-km access road, to support new rice fields (up to 1 million hectares planned), and sugarcane plantations for bioethanol (targeting 2 million hectares). While the exact extent remains uncertain, the planned expansion puts up to 3 million hectares of natural ecosystems at risk.

Navigate through “Papua Watch”, an interactive story map that tracks the ongoing expansion of food estates, oil palm and pulpwood plantations, mining, and infrastructure across 13 locations in Papua.

Simultaneously, oil palm concessions continue to expand across Papua, and nickel mining operations are advancing on small islands in Raja Ampat. These developments continue the trend observed since the early 2000s.

Over the past two decades, Papua — particularly Merauke and Sorong Regencies — has seen the steady spread of oil palm and pulpwood plantations, enabled by roads like the Trans-Papua Highway, a network of roads connecting North and South, East and West of this large island. Projects such as the controversial Tanah Merah scheme in Boven Digul Regency and the 2012 MIFEE food estate program, initially focused on rice and sugarcane, ultimately led to large-scale conversion to monoculture oil palm and acacia plantations.

The renewed momentum seen in 2024 signals a new phase of pressure on Papua’s forests, which still is one of the world’s last intact tropical wilderness areas.

Using maps, satellite imagery, and land use plan data, we examined the scale and pace of land clearing in Merauke and the wider Papua landscape during 2024, and the first half of 2025 — identifying where kand clearing occurs, which ecosystems are being lost, and the projects and companies behind the change.

Deforestation trends and drivers in Papua (Indonesian New Guinea)

The loss of ol-growth (‘primary’) forest in Papua rose by roughly 10 % year‑on‑year, from 22,500 ha in 2023 to 25,300 ha in 2024. The uptick is modest in absolute terms and still well below the 2015 peak that coincided with a spike in oil‑palm and roads expansion and widespread fire. Our Preliminary data (below) for 2025 suggests this trend is accelerating. By contrast, forest loss declined on Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi in 2024, emphasising Papua’s growing share of Indonesia’s remaining primary‑forest clearance.

Our satellite-based analysis identifies six primary drivers of forest loss in 2024 and four confirmed drivers for the first half of 2025 across Papua. Among these, the National Strategic Project (PSN) in Merauke emerged as the leading cause of deforestation in 2024, accounting for 24% of total recorded primary forest loss (5,936 ha). As of June 2025, we find that an additional 3,899 ha of forest has been cleared by the PSN initiative.

Since its launch around March 2024, the PSN in Merauke has resulted in the permanent conversion of 22,272 ha of land — affecting a range of ecosystems, including Melaleuca swamp forests, natural grasslands, wooded savannas, mangroves and dense primary forests, some of which may grow on deep peat soils.

Table 1. Drivers of Land Clearing in Papua, 2024–2025

This table summarises forest loss and total land clearing by driver for the years 2024 and 2025 across Papua. Forest loss refers specifically to areas with evergreen primary forest cover removed, while total land clearing includes all types of natural ecosystems—such as grasslands, swamp melaleuca, and wooded savannas—converted for industrial or infrastructure purposes. Percentages for 2024 indicate each driver’s share of total forest loss or land clearing. Data for 2025 remains incomplete, with some drivers (e.g., fire, other) yet to be quantified.

| Driver | Forest Loss 2024 (ha) | Total* Land Clearing 2024 (ha) | Forest Loss first–half 2025 (ha) | Total* Land Clearing first-half 2025 (ha) |

| Industrial oil palm plantations | 3,577 (14%) | 4,125 | 3,288 | 3,566 |

| Industrial pulpwood plantations | 20 (0%) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| PSN (road, seaport, rice, sugarcane, food) | 5,936 (24%) | 11,705 | 3,899 | 10,567 |

| Mining | 188 (1%) | 244 | 103 | 146 |

| Selective natural timber extraction | 4,890 (19%) | 4,890 | no data | no data |

| Roads + population centres | 1,386 (5%) | 2,339 | no data | no data |

| Fire | 458 (2%) | 8,195 | processing | processing |

| Other drivers° | 8,851 (35%) | still processing | no data | no data |

| All drivers | 25,305 (100%) | still processing | no data | no data |

*Natural grasslands, wooded savanna, and swamp Melaleuca vegetation are included in ‘Total’. °Other drivers include natural causes, smallholder deforestation, cryptic small scale mining, see this paper.

Industrial oil palm expansion was the second-largest driver of permanent conversion in 2024, responsible for 3,577 ha (14%) of permanent forest loss, below the long-term average (28%, 2001–2019) mostly in Sorong regency. Notably, oil palm-driven clearing in the first half of 2025 has already equalled the total loss from all of 2024, suggesting acceleration.

Selective natural timber extraction accounted for 19% of forest loss (4,890 ha) in 2024. While significant in area, this form of clearing is temporary, with logged forests often regenerating rapidly.

Fire was another driver in 2024, burning 8,195 ha of land, predominantly natural grasslands and savannas in Merauke. Only 458 ha of this total affected evergreen primary forests.

Industrial pulpwood expansion (e.g., acacia plantations) contributed almost no new forest loss in 2024 or the first half of 2025, marking a pause in what was a major driver of permanent deforestation in prior years.

While we could not fully map all artisanal mining, current satellite data shows little deforestation linked to mining in terms of area, also marking a pause compared to previous years, when tailings expansion from PT Freeport was a major driver. However, we confirm renewed mining activity on fragile, biodiversity-rich small islands (Raja Ampat) within the Coral Triangle, the world’s richest coral ecosystem.

We now examine specific cases in detail, breaking down deforestation and land clearing figures to provide deeper insight into how, where, and who drives current forest loss.

1. Infrastructure Rollout for Food Estate: Roads, Seaport, Rice

Operations for the PSN (Proyek Strategis Nasional) Food Estate began in August 2024, with hundreds of excavators deployed to the villages of Wanam and Wogikel, the core of the expansion zone. The project includes the construction of a logistics seaport and a 135 km east–west road across Merauke, the southeasternmost regency of Indonesia. The road is built to facilitate the development of a 1 Mha rice project, but the exact location of this project is not clear.

By June 2025:

- 6,431 hectares of land—primarily Melaleuca swamp forest—has been cleared by the Jhonlin Group, aided by the Indonesian military on both sides of this road.

- 40 km of the planned 135 km road had been constructed, with visible clearing along the corridor that aligns with planning documents obtained from Pusaka.

- The road plan stops just 1 km short of the Danau Bian Protected Area, a high-conservation-value wetland landscape.

- Indonesian government claims first successful harvest on a 4-hectare plot in May 2025 in Wanam and Wogikel villages. We caution that initial rice harvests after clearing forest often succeed due to residual soil nutrients, but yields typically decline over time as soils become acidic and nutrient-poor, especially in tropical wetland regions like Merauke.

This infrastructure corridor cuts through fire-prone peatlands and seasonally flooded wetlands. Roads act as hydrological wedges, draining wetlands, altering fire regimes, and increasing the vulnerability of protected ecosystems such as Danau Bian. If extended, this new PSN road could eventually connect with the Trans-Papua Highway (20 km east) and it is already planned to intersect the MIFEE road, forming a continuous access corridor across the wilderness.

2. Agribusiness Expansion: Sugarcane and the Bioethanol Strategy

The PSN project also includes nine new strategic sugarcane concessions, centered on old transmigration sites established in the 1990s. These concessions surround Danau Bian and Bupul Nature Reserves and form part of Indonesia’s national bioethanol plan. Two sugarcane expansion projects out of nine are currently underway. They are along transmigration sites and Trans Papua Road, and bordering Wasur National Park

2.1 Key Actors and Impacts

- PT Global Papua Abadi (GPA): Operating on ~50,000 ha, GPA cleared 11,751 ha of land between Jan 2024 and Jun 2025—4,404 ha primary evergreen forest and 7,347 ha wooded savanna. Investigations by Pusaka link GPA’s director and Sulaidy to the Fangiono family, which controls First Resources.

- PT Murni Nusantara Mandiri (MNM): Operating on 52,000 ha, MNM cleared 1,340 ha during the same period, also a mix of primary forest and wooded savanna. MNM borders Bupul Nature Reserve and is likewise tied to the Fangiono network, according to investigations by Pusaka.

Seven additional concessions remain inactive but could rapidly develop once road access improves along the TransPapua road.

3. Revival of Transmigration and Rice Cultivation

The PSN corridor appears to be enabling a renewed phase of transmigration, particularly in Semangga and Kurik, where programs began in the 1990s. Between Jan 2024 and Jun 2025:

- The Indonesian government cleared 2,721 ha for rice cultivation—mostly grassland and wooded savanna with up to 50% canopy cover.

- These sub-districts host a large transmigrant population, and the new land clearing has triggered protests by Indigenous communities (Yei, Malind, Maklew, Khimaima), who demand Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC).

- Several operations were carried out under military supervision.

Although framed around food security and national unity, the zone traverses flood- and fire-prone acidic peatlands where previous food estate schemes have failed. The current development model risks repeating those failures, prioritizing access and land speculation over sustainable agriculture.

4. Continuing Oil Palm Expansion

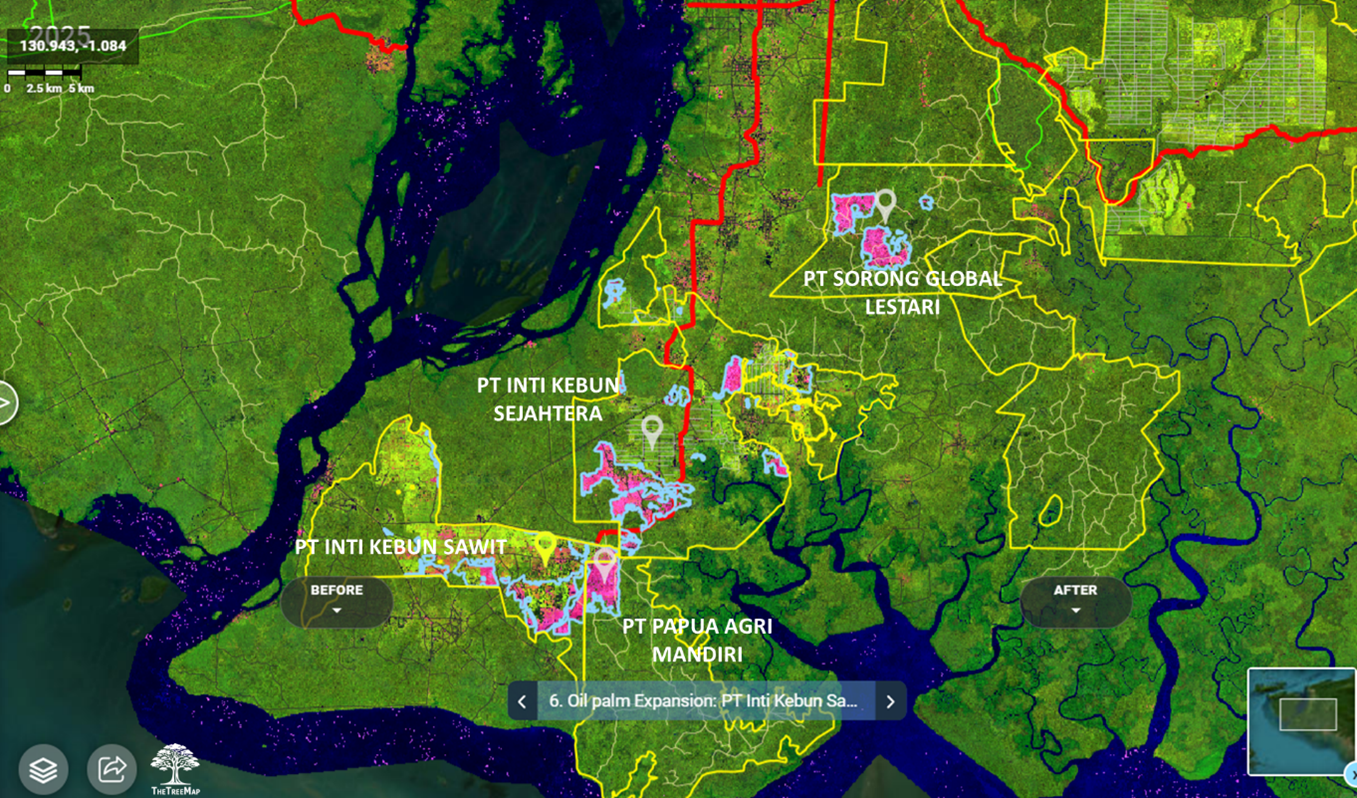

Although recent attention has centered on sugarcane, rice, and PSN projects, oil palm remains a major driver of deforestation, especially in Sorong, where clearing has continued steadily since 2020, and to a lesser extent in Merauke, Teluk Bintuni, and Jayapura. Since 2020, long-standing concessions PT Inti Kebun Sawit and Inti Kebun Sejahtera have cleared over 8,000 hectares of forest, with activity intensifying in 2024–2025. In 2025, two additional concessions in Sorong began land clearing for the first time. Palm oil-driven deforestation in the first half of 2025 has already equaled the total for all of 2024, signaling a likely surge by year’s end. Investigations by Pusaka link these concessions either to the CAA/Fangiono or Salim group, with one concession tied to the Korindo group in Merauke.

4.1 Merauke

- PT Dongin Prabhawa (DP): Cleared 538 ha of primary evergreen forest between Jan 2024 and Jun 2025, part of a resumed plasma expansion. The concession (37,000 ha) belongs to the Korindo Group, active in oil palm and pulpwood since 2011.

4.2 Sorong

- PT Sorong Global Lestari (SGL): After years of inactivity, began clearing in Feb 2025. By June, it had cleared 1,141 ha, including 1,023 ha of primary forest. It is reportedly controlled by the Fangiono family via PT FNG Boga Nusantara.

- PT Papua Agri Mandiri (PAM): Cleared 679 ha (including 634 ha primary forest) in early 2025. PAM is linked to the Fangiono family through the Ciliandry Anky Abadi (CAA) group.

- PT Inti Kebun Sejahtera (IKSJ): Cleared 2,480 ha (2,273 ha primary forest). IKSJ has a long history of conversion and was acquired by CAA around 2020. Reports cite ongoing permit irregularities, unauthorized clearing, and land conflicts.

- PT Inti Kebun Sawit (IKS): Cleared 2,170 ha (1,963 ha primary forest) during the same period. Also under CAA control, IKS shows similar patterns of community conflict and regulatory lapses.

4.3 Other Provinces

- PT Subur Karunia Raya (SKR) – Teluk Bintuni: Cleared 243 ha, including 178 ha of primary forest. Owned by Mulia Abadi Lestari, part of the Salim Group. Land disputes with under-compensated Indigenous communities are ongoing.

- PT Permata Nusa Mandiri (PNM) – Jayapura: Despite its forest release permit being revoked in 2022, the company cleared 187 ha (174 ha primary forest) between Jan 2024 and Jun 2025. Linked to the Salim Group through shell entities. Satellite and field reports confirm continued clearing.

5. Mining

While most attention remains on infrastructure and agribusiness, nickel mining continues to drive land clearing, especially on the small, ecologically sensitive islands of Raja Ampat.

• PT Gag Nikel – Gag Island (Raja Ampat): Cleared 35 ha between Jan 2024 and Jun 2025, in addition to 222 ha cleared between 2018 and 2023. Owned by state-owned PT Aneka Tambang (Antam) and operating under a Contract of Work valid through 2047. Although operating legally outside the UNESCO geopark, its continued activity sparked protests that contributed to the June 2025 suspension of several mining operations in Raja Ampat.

• PT Kawei Sejahtera Mining (KSM) – Kawe Island (Raja Ampat): Cleared 35 ha between Jan 2024 and Jun 2025, on top of 55 ha cleared between 2007 and 2010. Privately owned by the Aguan family through direct ownership and executive control. In June 2025, the company’s permit was revoked for environmental violations including deforestation, sedimentation, and unauthorized activity inside a UNESCO-designated geopark.

These concessions are part of a broader mining presence in Raja Ampat, where five known nickel projects overlap high-biodiversity zones. Mounting public pressure, led by Greenpeace’s 2025 “Save Raja Ampat” campaign, is calling for a permanent ban on island-based mining to protect these globally significant ecosystems.

Conclusion

Marketed as a food security initiative, the PSN corridor in Papua is rapidly transforming into a multi-commodity frontier — driven by sugarcane, and rice. In just 18 months, over 22,272 hectares of natural ecosystems have been cleared in Merauke by the PSN, including primary forest, swamp, and savanna. While this is substantial, it remains a fraction of the projected 3 million hectares targeted for rice and sugarcane development. Yet the threat lies in what may soon follow.

If the new 135 km PSN road built by Jhonlin is completed as planned — and then perhaps extended to connect to nearby roads — its ecological impact could grow significantly:

- As planned, the road would end less than 1 km from the Danau Bian Nature Reserve, putting this protected area at immediate risk.

- Just 20 km to the east lies the Trans-Papua Highway; if linked, the new road would become part of a broader network, opening up wider access to remote forest areas.

- The MIFEE road, built in 2012 and still maintained, intersects the new PSN route around KM 60, creating a continuous road corridor across southern Papua (see Figure 1).

A continuous corridor formed by connecting these roads would carve through southern Papua’s wilderness, unlocking access to previously remote areas. This would:

- Increase accessibility into Danau Bian, Bupul nature reserves, and Wasur national park, and facilitate encroachments in these protected areas

- Compromise the rights of indigenous peoples who oppose these plans and proposes weak safeguards against unchecked transmigrantions

- Accelerate speculative land clearing near roads by migrants, small and larger businesses (land rent goes up with roads)

- Facilitate the expansion of existing transmigration sites, such as those in Semangga and Kurik subdistricts, and those around the sugarcane concessions, with population growth of Merauke city nearby

- Enable industrial-scale agribusiness development, movement of commodities, with a new logistic port in Wanam and Wogikel, and new road access for the Jhonlin, Fangiono and Salim corporate networks.

The PSN Merauke project is framed as a step toward food security and national unity. Setting aside the environmental and social concerns of such a project, a critical question is whether it makes sense to try to grow rice in Merauke’s swamps.

Merauke Regency has a tropical wet and dry savanna climate (Köppen classification: Aw), marked by extended wet and dry seasons, making precise irrigation systems essential for successful rice cultivation.

Wildfires naturally occur each year during the prolonged dry season, with increased intensity during El Niño years. Draining the wetlands could exacerbate the frequency and scale of these fires. Without waterlogged soils to suppress ignition, flames could spread rapidly across the landscape—and if peat is present, the risk of uncontrollable fires would be significantly higher.

Moreover, the soil conditions of the Melaleuca wetlands may pose additional challenges. These soils have high acidity — conditions far from ideal for rice cultivation. If peat soils are present, rice farming will be even more difficult, as their high acidity and low fertility create a harsh environment for crops. Without careful management and suitable soil amendments, rice farming in these wetlands will likely face significant obstacles.

The Indonesian government claims a successful first rice harvest on a 4-hectare plot in May 2025 in Wanam and Wogikel villages. But this initial yield is no guarantee of long-term viability. Early rice harvests after forest clearing can succeed due to residual soil nutrients, yet productivity typically declines as tropical soils turn acidic and nutrient-poor.

This new road corridor will cut through swamplands prone to flooding and fire, underlain by acidic soils and peat, conditions that have caused past food estate projects in Kalimantan and elsewhere to fail. While marketed as a boost for agriculture. The corridor is better suited to enabling agribusiness expansion, land speculation, and extractive industries, and control over the region, than to supporting sustainable rice cultivation and bioethanol production.

At the same time, industrial palm oil remains a leading driver of deforestation. In the first half of 2025 alone, oil palm-driven clearing has already matched the total from all of 2024, suggesting that 2025 could become a bad year for oil palm deforestation in Papua. The CAA/Fangiono and Salim corporate networks are driving this growth. These groups have not made any pledge to end deforestation.

Meanwhile, nickel mining is rapidly emerging as another major threat, especially on the small, ecologically sensitive islands of Raja Ampat. Companies like PT Gag Nikel and PT Kawei Sejahtera Mining have resumed or continued operations, clearing land and sparking protests from Indigenous communities and environmental groups. These operations violate the ecological integrity of small islands, which are physically limited, erosion-prone, and home to globally significant biodiversity. Once damaged, these island ecosystems cannot regenerate at scale. Industrial mining on small islands is not only high risk—it is fundamentally incompatible with sustainability.

Without urgent course correction, and renewed political will anchored in Indigenous land rights, science-based land use planning, a permanent halt of the Merauke Food Estate, a moratorium on forest conversion to oil palm, and ban on island mining, Papua risks losing more ecosystems that cannot be restored, for returns that will not last and not be shared equitably, and Indonesia may risk jeopardizing its 2030 net zero target.