VIEW IN ATLAS Patches of rainforest in deforested land within Tesso Nilo National Park in Ukui, Riau.

VIEW IN ATLAS Patches of rainforest in deforested land within Tesso Nilo National Park in Ukui, Riau. The vanishing forests of Tesso Nilo National Park

VIEW IN ATLAS Patches of rainforest in deforested land within Tesso Nilo National Park in Ukui, Riau.

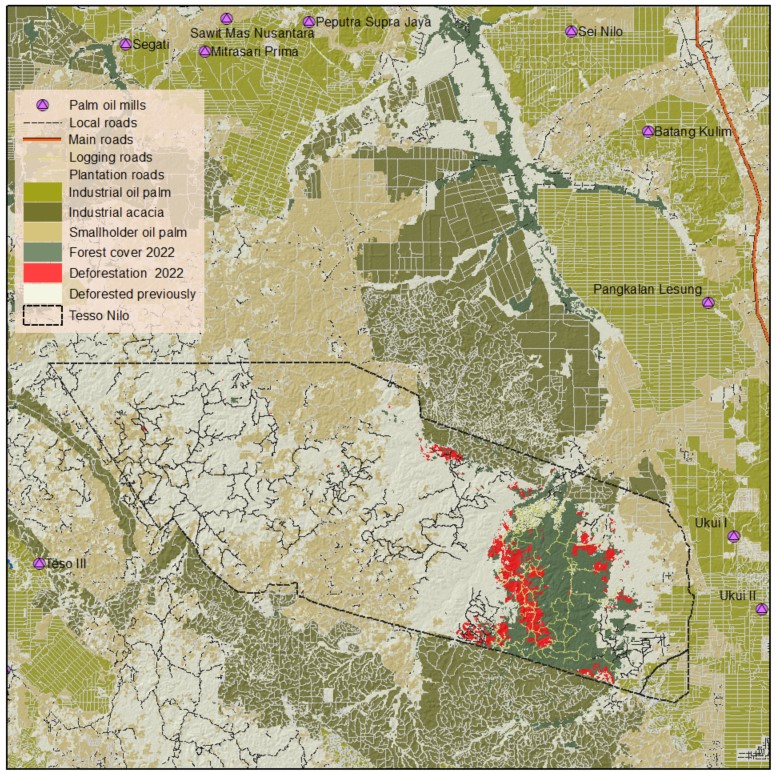

VIEW IN ATLAS Patches of rainforest in deforested land within Tesso Nilo National Park in Ukui, Riau. Palm oil-driven deforestation in Indonesia slowed to a 20-year low in 2021 and is stabilizing in 2022. It is good news, but we see worrying developments in Tesso Nilo National Park, Riau Province, Sumatra.

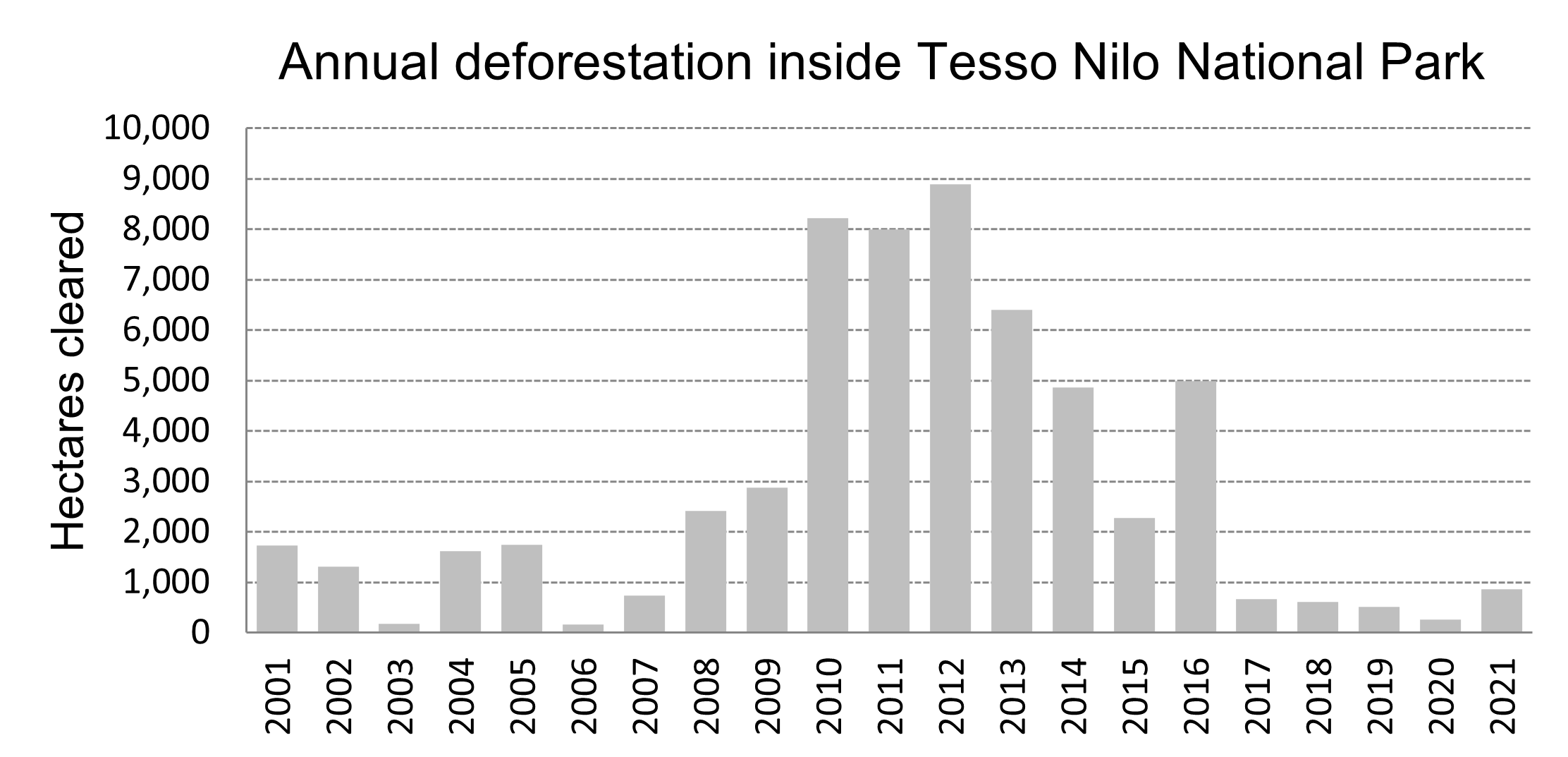

Deforestation is accelerating again in Tesso Nilo. Despite genuine and dedicated conservation efforts by the Park Office, the rampant, and illegal clearing of forests inside the Park is surging in 2022.

Analysis by TheTreeMap, conducted using Sentinel-2 and Planet/NICFI, reveals that the Park lost 2,774 ha of primary forest since January 2022 (until September 2022), representing a three-fold increase from last year.

Deforestation inside the park is well known to be connected to palm oil production, and its global demand.

According to the Park Office, the natural forest in Tesso Nilo extended 13,000 hectares at the end of 2021, while 41,000 ha were planted with oil palm and 28,000 ha were idle land, overgrown with shrubs.

Tesso Nilo is surrounded by industrial plantations, acacia and oil palm. Several investigations by Eyes on the Forest since 2011 found that 22 crude palm oil (CPO) mills, all connected to the most prominent traders and many international buyers with no-deforestation commitments, acquired illegal palm fruit from Tesso Nilo at some point in time. A local newspaper concluded in July 2021 that PT Mitrasari Prima mill is processing palm oil fruits from Tesso Nilo. This mill supplies CPO and PKO to GAR and Musim Mas, and Wilmar, with sustainability commitments.

The challenges the Park Office faces today are conflicts over land ownership, corruption and pressure from the growing global demands for palm oil.

Investments in industrial plantations around the Park brought massive industrialisation of the landscape, new processing plants, roads and other infrastructures, attracted workers and their families from elsewhere, requiring more infrastructure and thus more land and inevitably more deforestation risk on the Park.

The park is a former logging concession with old roads, which over the years muddied the legitimacy of the Park, and attracted migrant communities. A local investigation reported that a village chief recently issued thousands of land certificates inside the Park, and did not see any wrong doing. It is clear that many communities dispute ownership of the Park, with sometimes legitimate reasons when this is their ancestral lands.

A land mafia, well connected wealthy individuals is also known to acquire land inside the Park.

Established in 2004 to conserve some of the last lowland dipterocarp forests of Sumatra, Tesso Nilo National Park (81,000 ha) is today a mere shadow of its former self. Since its creation in 2004, the park lost 80 per cent of its forest area.